YES Network’s Jack Curry discusses the legendary 1998 Yankees | Q&A

We all know the 1998 Yankees were a special type of championship team, and now Jack Curry has the full story.

The former New York Times columnist and current YES Network analyst says as much in the title of his new book. The 1998 Yankees: The Inside Story of the Greatest Baseball Team Ever comes out May 2 from Twelve, part of the Hachette Book Group.

And for those who fondly look back on the ’98 Yankees, even 25 years later, there’s plenty of awesome stories.

How did Scott Brosius become perhaps the best player to be named later ever received in a trade? Just how much of a pitching enigma was Orlando “El Duque” Hernandez? How did manager Joe Torre and team leader David Cone manage a literal All-Star cast of wildly different clubhouse characters?

And how about David Wells throwing a perfect game after partying all night with a certain Saturday Night Live alum?

Some may recall I spoke with Jack Curry back in 2020 about his book he wrote with Cone. After reading his story of baseball’s best team, we shared our own memories of that championship season.

Josh Benjamin: So, Jack, the last time you and I spoke was the summer of 2020 when we discussed your book with David Cone. Baseball was slowly starting to come back together. It’s now three years later. Do you find now that you have a new appreciation for the game?

Jack Curry: Oh, 100%. I think anyone who says that they don’t that they’d be lying. You’re taking us back to some of those darkest days when all of our lives were thrown upside down. Many people lost loved ones. To talk about baseball sometimes felt trite, to wonder if the game was coming back. But now that we have it, you’re right. You grasp onto it even more. I had not been to spring training for a couple of years and this spring, just to walk back into that ballpark again? To walk on the field, to go in the clubhouse? Hey, this is what I do. So I missed that. So without a doubt, it’s a wonderful feeling to be able to cover a 162-game season, to be at the ballpark, to be in the clubhouse, or the press box or the broadcast booth. It’s a great feeling.

JB: Kicking right off at the start of the book, right after Game 5 of the 1997 ALDS against the then-Indians. You’re there. Teams suffer bad losses all the time, but the ‘97 Yankees were a Wild Card team after the Red Sox finished in first place. How was this bad loss different from the other disappointing ones over the course of that season?

JC: Josh, I’ve covered baseball for more than 30 years and I’ve been in some losing World Series clubhouses. So to your point, you’d think that would be more miserable, more morose than losing in the round that they lost. There was just something about that team after having won in ‘96. I think they thought they were going to be on another magic carpet ride. They weren’t just throwing their gloves on the field. They knew they had to perform. But they were in a position to win and Mariano (Rivera) gives up the home run to (Sandy) Alomar Jr.

So I think it was a combination of being stunned, and being morose, and the season just ending so abruptly. Because (Paul) O’Neill’s got the double off (Jose) Mesa, then Bernie Williams comes up. He’s a single away from tying it, and he hits this lazy fly ball to center field. And I just went from locker to locker interviewing guys, and I couldn’t believe how much heartache was coming out of their voice and coming out of their body language. And a lot of those guys were committed in the offseason to work so hard that that would never happen again. And that’s why I felt it was appropriate to start a book about the ‘98 Yankees with what happened at the end of ‘97.

JB: I remember very distinctly Paul O’Neill just kind of hunched over at his locker. This was at the start of the ‘98 World Series VHS that ultimately came out. And he just said, “The feeling here? It’s not good.”

JC: I quote him in the book and I was around that scrum. He said something along the lines of, “This is going to take four months to get over.”

And if you do the math, that’s taking you right to spring training. So he was basically telling you he was going to be miserable through Halloween, Thanksgiving, Christmas, New Year’s. And it stung. And I think (Joe) Torre sensed that when spring training came around in ‘98. Some people have asked me, “What was Torre’s role in managing this team?” Well, I’ve asked Joe: What was your role? And Joe said that he sensed from the beginning how committed these guys were, that they felt they left something on the table in ‘97.

JB: Joe Torre was the Hall of Fame manager of this team, almost avuncular in how he ran the clubhouse. Don Zimmer, the bench coach, it’s his job to take care of the manager. The leader among the players, as we discussed a few years ago, was David Cone. This was right when you were getting to know him, too.

There were tons of personalities in that clubhouse. Derek Jeter and Jorge Posada were both obsessed with winning. Bernie Williams quietly played his guitar while David Wells was a rebel. Darryl Strawberry was diagnosed with cancer right before the playoffs, and the season itself started badly. How does someone like David Cone manage all of those personalities all at once?

JC: I’m glad you said what you said about Cone and remembered our conversation. Because I’ve done some interviews for this book where some people have been a little surprised when I’ve talked about Cone’s role. He loved being in the middle of things, Josh. He told me as a starting pitcher, what are you going to make? 32 or 33 starts a year? There’s 130 games that you can impact in some way.

So I think Cone felt it was his mission to get to know his teammates well, observe the other team. If there was a guy who was feeling down, Cone wanted to be there to lift him up. ANd if you took a poll of that ‘98 team and said, “Who was the most popular guy in that clubhouse?” It would be David Cone. There’s no doubt in my mind that Cone would win that award.

He wanted to be a sportswriter growing up. Obviously, he wanted to be a pitcher, but he loved Oscar Madison and I think that just carried over when he got to the major leagues. That he loved the interaction with the media. And when he did it, maybe he kept it away from someone like O’Neill who didn’t want to talk every day.

JB: A team full of personalities united by one common goal. Meanwhile, as we celebrate the 25th anniversary of this team, general manager Brian Cashman has also had his job for 25 years. How patient a man is he to have George Steinbrenner breathing down his neck from the get-go, and to still be here 25 years later as probably the greatest in the game?

JC: It’s one of the greatest executive runs probably in New York sports history. In the book, I describe how Cashman didn’t want the job. He seemed resigned and Steinbrenner met with Cashman and said, “I can recycle someone, but I’ve been told that you can handle this job and I want to give it to you.”

Brian said, “I didn’t want it, but I was smart enough not to turn it down.”

So I think it says a lot about his patience and his resolve and his success that he is still here to this point. Under his stewardship, there’s only been three years, I believe, where the Yankees haven’t made the playoffs. They haven’t won since ‘09. Cash will be the first one to tell you that that’s a problem. They want to change that. They think 2017 should have an asterisk next to it. I know Brian Cashman and his staff burn to win a title soon.

JB: You’ve mentioned having a good relationship with George Steinbrenner. Did you speak with him often during the ‘98 season?

JC: Josh, if you were not calling George a lot as a New York baseball writer, you weren’t doing your job. So though I can’t remember these ten specific conversations, I definitely know I talked to him about that team. And George was a perfectionist. There’s a point early in the book where I mention that George said to Joe Torre, “Has a team ever gone 162-0?”

That was obviously tongue-in-cheek, but George had a football background. And there have been football teams that had been undefeated. I think there was a message that George was sending. “This team is built to be very, very successful. How are you going to get it there?”

JB: Going back to David Cone and his leadership, this is really the first year where we really start to notice Derek Jeter. As a leader himself, how much did Cone respect Derek Jeter back then and also today?

JC: Cone told me that Jeter started out in ‘96 as sort of the fawn trying to get his legs under him, trying to figure out who he was. By the ‘96 postseason, Cone said that Jeter was one of the leaders on the team. And I think where Cone helped Jeter’s maturation, or Jeter’s ability to become who he did was– in the ‘90s, and you see this sometimes now and it’s so hokey and so stupid, they would haze players.

And Cone was a big proponent of saying in ‘96, “Hey, we need this kid to succeed. We need a young shortstop to excel for us. Why are we messing around with ‘Oh, he’s gotta wear this outfit on a plane. He has to get so-and-so’s gum and carry this guy’s suitcase.’”

And so Cone was very, very strongly saying, “Hey, let’s make sure this doesn’t happen. Let’s let this kid play.”

JB: Let’s talk about Scott Brosius. He overachieved in 1998 compared to the rest of his career, but what a player and what a season! He had a .300 season, hit .340 in what Baseball-Reference calls “late and close” situations. It’s strange because Scott Brosius is almost still on the Yankees today, but his name is DJ LeMahieu.

JC: That’s a good comp! That’s a great call and I think Brosius felt liberated coming to New York. It sounds so weird. You would think in Oakland, where there was less pressure, that you wouldn’t be liberated coming to New York. But he said to reporters early that season about, “You go to Oakland and there’s 7,000 people in the stands, and you feel like you’re playing in a minor league game. You come to the Yankees, and there’s 40,000-50,000 people every night, and they’re reminding you how important it was.”

I think Torre had a stroke of genius early in that season. He played Brosius every day. He told Luis Sojo, who later fractured his hand and lost his roster spot to Homer Bush, “You’re not going to play in April. Jeter, and Knoblauch, and Tino are going to play every day. And I’ve got to play Brosius every day. I have to see what I have.”

Well, guess what? He found out what he had and then Brosius wound up playing I believe more innings than anybody on the team that season.

JB: And at the same time, Dale Svuem was a secret “glue guy” in his own way.

JC: Yes! He’s an interesting story because the Yankees signed him as protection or insurance if Brosius sputtered. Brosius never sputtered, so Dale never played. Dale said he went to the ballpark everyday kind of as the 25th man on the roster thinking he was going to lose his spot, and eventually he does. But I’ve never seen this before. He goes from being a guy on the roster to sticking around as a batting practice pitcher and a bullpen catcher because he recognized how special that team was. He wanted to continue along that journey.

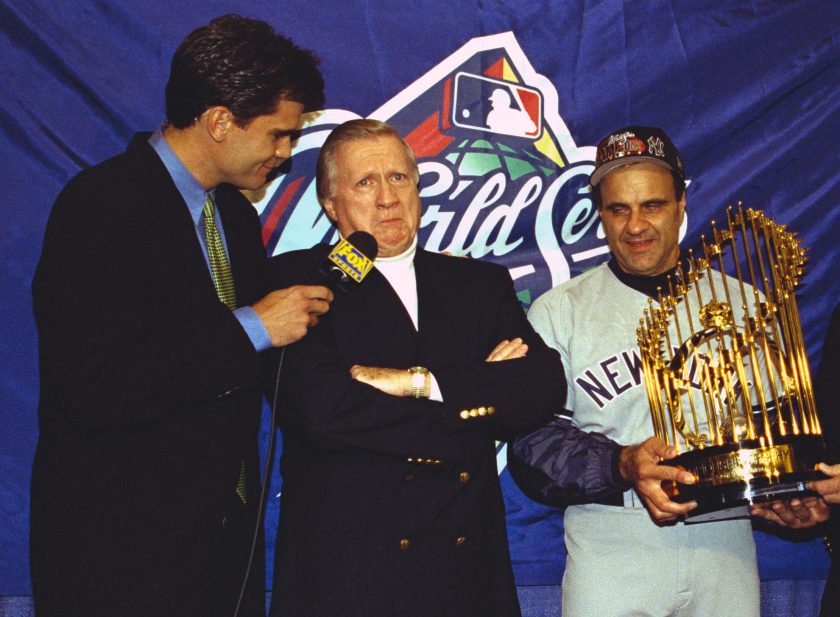

JB: We’re really going to go back in time for this one, Jack. It’s Game 4 of the ‘98 World Series at the old Qualcomm Stadium. The final out’s been made. Take us through that moment, just the aftermath of going down from the pressbox, down into the clubhouse in the midst of that celebration. Describe the chaos.

JC: Well, the clubhouse is not big, first of all. So you start talking about how many players and coaches and executives you already have. Then, you add all the media in there. So it really felt as if you were in a D-train at rush hour. It was packed. And you’re moving from spot to spot trying to get interviews.

But what stood out for me was how happy that team was, but also how relieved they were. Because if you win 114 games and you don’t win a World Series, nobody remembers you. The Seattle Mariners won 116 in 2001. Who talks about them? Nobody. So I think the Yankees were just overjoyed, but also relieved that they completed the deal. They got the 11 postseason wins and they made sure that a special season would remain special forever.

JB: Talking about relief, the story of Orlando “El Duque” Hernandez. That big game in the ALCS. In a way, you can see that David Cone would almost view him as a pitching kindred spirit just from the funky arm slots and different pitch grips. He overachieved, but still really mattered to that team. He showed up out of nowhere and was instantly a perfect fit.

JC: A gift from above for the Yankees, a tremendous signing. A guy who when he made his debut? John Flaherty, who I work with now at YES, was on Tampa Bay. And he said the scouting report they got on June 3, 1998 was, “Fastball is average. Has some breaking pitches, but not overwhelming.”

And essentially, this guy was a mediocre pitcher. And then Flash said they didn’t factor in the motion, his ability to hide the ball. His ability to pitch to the corners, how tough he was, how he never gave in. He was going to make you swing at his pitch so yeah. He stands out as one of my favorite players on that team and someone I loved covering. I loved covering him on and off the field because in his early years, he didn’t necessarily know that a pitcher wasn’t supposed to talk before his start. So we got a big dose of El Duque before starts.

JB: Jack, this truly was a special season. We haven’t seen anything close to it since. Baseball has changed now and grinding out at-bats for either a walk, a hit by pitch, or a single; it’s more power-oriented. Pitching is more based on velocity as opposed to “Can this guy get people out?”

25 years later, do you ever find yourself lamenting how we’re never really going to see that ever again?

JC: That’s a great question, Josh. I always want to be a glass half-full guy. I like the current changes in baseball. I love the pitch clock. I like the shorter bases because it’s added action. Originally, I was against eliminating extreme shifts. Now, I’m on board.

I don’t know if I would say lament, but I do look at this ‘98 team and how it would stack up against any team 25 years later. And I think they would stack up wonderfully. I think whatever adjustments they had to make, they would have made them. You talked about grinding out at-bats. I mean, this team was the king of that.

I interviewed Jason Varitek for this book and he was a rookie with the Red Sox in ‘98. And he just talked about how they were relentless, and you couldn’t get them to chase a bad pitch. I think about that when I think about the ‘98 team.

Follow ESNY on Twitter @elitesportsny

Josh Benjamin has been a staff writer at ESNY since 2018. He has had opinions about everything, especially the Yankees and Knicks. He co-hosts the “Bleacher Creatures” podcast and is always looking for new pieces of sports history to uncover, usually with a Yankee Tavern chicken parm sub in hand.