New York Yankees: Jack Curry shares thoughts on David Cone, pitching, and more (Exclusive)

YES Network’s New York Yankees analyst Jack Curry sits down with ESNY to discuss the book he wrote with former fan favorite David Cone.

[sc name=”josh-benjamin-banner” ]Pitching is an art.

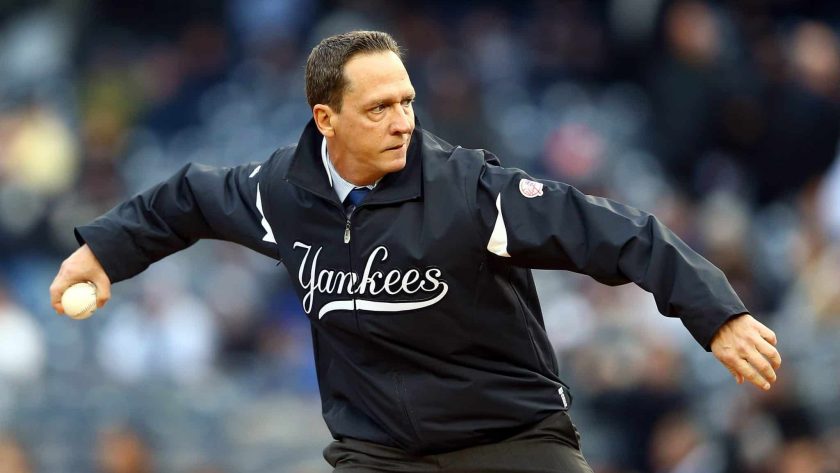

This is what Jack Curry calls the biggest takeaway from his book with former New York Yankees and New York Mets pitcher David Cone. The book, Full Count: The Education of a Pitcher, was published last year and is now available in paperback from Grand Central Publishing.

But Full Count isn’t your average baseball book. Half a memoir and half a pitching manual, Cone takes us into his mind as he breaks down various vignettes from not just a 17-year career, but a life devoted to his craft. As he puts it, his “maniacal” approach made him unpredictable to opposing hitters and led to five World Series rings, as well as a perfect game.

And Cone’s co-pilot on this journey is the affable Jack Curry, longtime New York Times baseball beat writer turned YES Network analyst. After starting, as he puts it, a pitching journey, this project evolved into a more personal one between him and his subject.

I was fortunate enough to spend some time speaking with Curry, and discussed everything from his and Cone’s book to life on the beat. Jack Curry also had some valuable insight ahead of the unconventional 2020 season, further cementing his status as someone with their finger square on baseball’s pulse.

Baseball beginnings

Josh Benjamin: You grew up in Jersey City. Did you grow up a Yankees fan?

Jack Curry: It’s interesting that you ask that question. I have a brother who’s a couple of years older than me. I was born in 1964. So when I’m five years old, I have a seven-year-old brother who was watching the ’69 Mets. And I didn’t know what was going on. Because I was born in November, so I was actually four when the Mets won the World Series.

But I don’t know if you have any older siblings, but especially with my older brother, I followed in his footsteps. So as a kid, there was a lot of Mets love in our house. A lot of Tom Seaver, a lot of Ed Kranepool. A lot of John Milner. So I was a baseball fan through and through. But in the early days, following in my brother’s footsteps, it was a lot of blue and orange!

JB: I can understand that because even though I cover the Yankees and grew up a fan, my mom’s side of the family are all from Queens and Long Island. So they’re very much into the Mets!

JC: A lot of the guys I grew up with in my neighborhood were Mets fans, a couple of Yankee fans sprinkled in. But when I started covering baseball for The New York Times, objective is the way that you go. And it’s about the game. It’s about the story. It’s not about rooting. My wife has this memorized. We’ve been married for 28 years and when I was covering baseball for the Times, she would always say, “Jack roots for fast games and good stories.”

And obviously, now, I work for the YES Network. And when the Yankees are successful, that’s very good for our network and I’m not foolish enough not to realize that. But in my job in watching the game and analyzing the game, I can’t sit there and watch the game the way a fan would and perhaps root for an outcome. I have to, “OK, why did he throw a slider there? Why didn’t he throw his high fastball there? What did the hitter do right or wrong there?”

So I went down that objective road at a very young age, and I’ve remained there.

JB: You sound a lot like David [Cone] does in this book that you wrote together!

JC: Yeah, and David takes his broadcasting very seriously. And when we got to that point in the book and we were talking about it? I know the amount of work David puts in during his broadcasts, but he actually even surprised me a little bit about that sort of player dilemma. “I don’t want to sit here in the broadcast booth and just criticize guys because I know how hard this game is to play.”

But David also said, “You can’t be a fraud,” and if you see something that’s done incorrectly on a field or you disagree with a manager’s decision, you have to point that out. And I think he is terrific at doing that.

Life on the beat

JB: He really is. You also mentioned you were at The New York Times. When did they give you the Yankees beat?

JC: I started at the Times in 1987 and I started in a program that was called the Writing Program, which I don’t think even exists anymore. But it was a way to hire young journalists, and you were going to do a lot of clerical work. Answer phones, do research for other reporters. But if you showed enough hustle and enough initiative, you would get an opportunity to write.

So probably by 1990, I started covering baseball. But they also had me doing college football, college basketball. I took over the Yankees as a beat writer at the midway point of the 1991 season.

David Cone the player

JB: Now, by this point, you’re probably very much aware of who David Cone is because he’s starring across the river with the Mets?

JC: Very much aware. And in 1990, I had done some Mets and Yankees. As I said, the Times had me doing some baseball. I wasn’t exclusively a Yankee writer. I wouldn’t say that David and I were buddy-buddy or knew each other very well back then. But I absolutely was in the clubhouse and interviewed him and knew what he was about.

I really got to know him in ’95, when he came over to the Yankees in a trade. That’s the point where I started to get to know him. And I always appreciated his baseball talent. But the one thing I always tell people about David, and this is why I wanted to write a book with him, is he was a go-to guy in the clubhouse.

Whether you were talking about his slider, labor relations, Derek Jeter’s defense, Paul O’Neill’s swing, David Cone’s baseball knowledge would just jump out at you.

JB: That’s really what stood out to me in this book. David Cone is very emotionally intelligent but he’s got, as he put it, a “maniacal” side. He’s talking about after the 1993 season with the [Kansas City] Royals, where the wins aren’t quite there but he’s pitching well overall. That’s when he’s talking about sabermetrics. That was a shock to me because as far as I knew, sabermetrics and Moneyball didn’t really become a thing until Oakland in the early 21st century. And he’s talking about having access to the numbers in the ’90s!

JC: I think that he had access to the numbers. I don’t think it necessarily had the name “sabermetrics,” but we knew that was what he was referring to. He had a great strikeout-to-walk ratio. He wasn’t allowing a lot of hits per inning, and his ERA was down. I don’t think they had Adjusted ERA+ back then, but you’re right. The wins weren’t there because he was playing for a poor team and back then, that was how starting pitchers judged themselves.

So I think when he had an agent in Steve Fehr, who was Donald Fehr’s brother, and we know Donald Fehr led the players’ union for so long. Steve Fehr was one of the people who pointed that out to him. “Look at your numbers. These numbers are really, really good.”

And that even goes back to an arbitration hearing he had against the Mets, where the Mets challenged his salary figure because his won-loss record wasn’t great. But Steve Fehr brought all these other stats to the table about the games he could have won with a better offense, and Cone won that arbitration hearing.

JB: On a similar subject, this was actually my favorite part of the book. Just an incredibly emotional story from the 1992 Winter Meetings in Louisville, KY. The late, great Ewing Kauffman, while battling cancer, invites Cone to his hotel room and says, “You want to come home? Let’s not leave this room until we have a deal.”

That’s such an emotional and personal story to share!

JC: Let’s be blunt. He was dying at that point. He was lying in a hospital-type bed in the hotel, but it meant so much to him and the city of Kansas City that he wanted to bring a hometown hero back. David started his career with Kansas City, debuted in ’86, was traded before the ’87 season, had a lot of success, and it meant so much to Ewing Kauffman to have him back that he made that trip.

And you’re absolutely right. It’s an emotional story, and he gave him a contract that David couldn’t say no to. [He] included a $9 million signing bonus that gave David some protection against the imminent work stoppage which we eventually saw. But yes, David speaks very highly of Kauffman and said, “As a Kansas City kid, how could I not respect what this man was trying to do for his franchise?”

The Yankee years

JB: There’s so much to take away and learn from this book. I didn’t realize until I started reading that you also co-authored The Life You Imagine with Derek Jeter, one of my favorites. They’re several years apart, but I just looked at the two books side by side. They’re half memoir, half how-to. Did you use that same style and approach on purpose?

JC: It’s interesting. With the Jeter book, I was approached by Jeter and his people. And they kind of had an idea of how they wanted the book to go. Within the title, it says Life Lessons for Achieving Your Dreams.

I think with David, we started out on a pitching journey that even he has said once we sat down, it became more of a personal journey. But I never planned to try and mimic what we did with the Jeter book. I actually think the Cone book, for numerous reasons, has more depth to it. Jeter was 25, 26 years old when we did that book and three or four years into his career.

Cone’s career is over. He’s a 55 or 56-year-old man when we wrote that book. He’s talking about the pitfalls and the problems and the things he did wrong in his career. He’s got stories about his dad and his brother and coaches that he either got along with or didn’t get along with. So though I’m very proud of both books, I think the Cone book digs deeper into David’s life simply because we had a bigger canvas. We had 30 more years of life to talk about.

JB: Looking through the book, this was absolutely fascinating. He has almost an eidetic memory. He’s pinpointing the exact pitches to the exact hitter. The exact timeframe. I can’t think of what I had for lunch last week, let alone a pitch I threw in high school.

JC: It’s interesting. I found out about that too, and I don’t think David is alone in this way. The games that involved misery and a lack of joy are the ones that he remembered more than the games that he pitched wonderfully in. He focused or remembers the misery more than he remembers the joy. A lot of downtimes in his career, in games where he made mistakes, he was very detailed about those.

Now, we did a whole chapter on the perfect game, of course. But I remember reading one review where someone said something along the lines of, “Cone is going to take you to some of his darkest moments on the field where he failed, and we’ll rush past the season that he won 20 games.”

And I thought, “Actually, the reviewer kind of has that right,” because Cone expected to succeed. He expected to excel. That’s who he was. So in the moments where he failed, I think that’s where some of the emotion and some of the description really came out of him.

JB: You were still at the Times and on the beat when he threw the perfect game, right?

JC: I was.

JB: Were you there for it?

JC: (Laughing) I was not! I shouldn’t say I was on the beat. I covered the beat through ’97. I was a national baseball writer from ’98 on, but I still covered a lot of Yankees. If you were a national baseball writer in those days, the Yankees were the biggest national story. That happened on a weekend. I actually had that weekend off, and what a mistake! I regret not having been there and I regret not jumping up in the fifth inning or so. I live about a half-hour from Yankee Stadium. I should have dashed in!

JB: I remember watching that game. I was 13 and I was at home with my dad and my grandfather. And I remember what stood out to me most was that, as discussed in the book, there was a half-hour rain delay. Other pitchers would have been taken out, but no. Cone stayed in, and the rest is history.

JC: Stayed in and loves to tell the story of how he stayed warm by tossing a baseball in the corridor of Yankee Stadium with one of their batboys. A guy named Luigi who was a nice young man, and he plays a role in Cone’s perfect game. And Cone tells that story often. He’ll bring that up and how you needed to keep your arm warm during that rain delay.

Clubhouse life

JB: Let’s shift gears a little bit. You covered the Yankees for a while and two people who feature prominently [in the book] are David Wells and George Steinbrenner. Two of the most bombastic personalities in baseball history. It must have been an interesting time having the two of them plus Cone all sharing a clubhouse together.

JC: Yeah. I knew George well. I was fortunate in that from covering the Yankees since ’91. If you did not have a relationship with George, you were pretty useless to your news entity. Newspaper, radio station, magazine. And I was able to get George to return some of my phone calls. I tried to be fair as a beat writer. If there was something that deserved criticism, I would levy that criticism. But I was able to get George to return my phone calls, which was key.

Wells was a guy who I always thought as kind of like the guy in high school who just loved being in the locker room, loved being the prankster. Loved being a little bit of the Clown Prince. I got along with David. He didn’t bother me. There were some writers who he clashed with. I was not one of those.

I was able to have a relationship with him and interview him when I needed to. The dynamic between Steinbrenner and Wells was always interesting because they had a couple of blowups in their day where they almost got into a fight once. Wells talked about that in his book.

And Cone, in the midst of all that, was the sort of bodyguard, in a way. Or the protector. Wells and [Joe] Torre did not get along. And we detail this in the book where, at one point, Cone finally says to Torre in 1998, “Joe, let me have him. Just let me take over. I’ll watch over him.”

And Cone told me something that I had never heard. And when I talked to other people about it, they hadn’t heard about it. In that ’98 season, when the Yankees were the best team in the world, they would stay in a different hotel. Because Cone understood that Wells liked being a rebel. He liked his space. He didn’t want to come back at 2:00 in the morning whether he’d had a few drinks or not, and run into somebody in the lobby.

And it worked. I mean, look at those two guys and the numbers they put up that year, finishing third and fourth in the AL Cy Young. And obviously the Yankees won it all. So parting from the team and just doing their own thing worked out for them.

JB: You mentioned how once he came to Yankees in ’95, that’s when you really developed a relationship with Cone. Even though you were on the national beat by this point, did the budding friendship you had developed make his hard 2000 season all the more difficult to watch?

JC: I felt for David because I knew how much of a competitor he was, and how much of a perfectionist he was. And even more so, we talk about this in the book, how he was always a guy who could pull a rabbit out of the hat. He would drop down and throw a sidearm slider. Or he would take a little bit off a curveball.

He would just figure out a way to get out of a mess. And in that season, there was no rabbit out of the hat. And you could see how it bothered him, how it drained the life out of him. I talked to you about being a spokesman and always being there in a clubhouse. David receded that season. And it’s not that he didn’t want to talk to us about himself. I think he felt he wasn’t equipped to be a spokesman anymore because he wasn’t helping the team win.

So very difficult to see any athlete go through that. But a guy that you admire and a guy that you respect? Having to see that was tough. That season was horrible for him to have to go through.

The art of pitching

JB: I remember it being very hard as a fan too. I was only a teenager, but David Cone had become my favorite man on the pitching staff. I remember watching him pitch with my father. At two-strike counts, he would always say, “Watch. The at-bat’s over.”

It seemed nine times out of 10, the hitter either popped up or struck out. Watching such a complete 180 was shocking, to say the least.

JC: Yeah. I interviewed a couple of elite hitters, Ryne Sandberg and Paul Molitor, and they talked about facing Cone. You couldn’t out-guess him. Ryne Sandberg said to me, “He had a slider, but he had three different sliders because he would change arm angles. He would take something off of it.”

He said, “You couldn’t figure him out. So the best thing for me was to try and get something early in the count.”

Because as you just noted, and your dad noted, if you got to two strikes against Cone, he was going to win that battle. Unless he made a mistake and didn’t do exactly what he wanted to do, he was going to figure out a way to bury you.

JB: In the book’s afterword, you mentioned how you had a “doctorate in pitching” after writing it. What do you and David want people to take away from this book?

JC: That’s a great question. And you know what? In all the interviews we’ve done, and the hardcover came out in May of last year, I’m not sure anyone asked me that specific question. I want them to take away that pitching is an art. Just like any other craft and just like any other art that you try and excel at. And that David Cone, both statistically and mentally, put more into that craft and had more passion about that craft than anyone I’ve ever covered in 30 years of baseball.

I think he thought about pitching on and off the mound more than anyone I’ve ever encountered. And I’ve interviewed Greg Maddux and Tom Glavine. I interviewed them for the book and I know those guys thought about pitching 24/7. But I’ve interviewed Cone a lot more and I really believe that his world just revolved around pitching. And he was going to figure out a way to get you out. He was going to outwit you, he was going to out-guess you.

And post-career, though he’s not throwing a baseball anymore, I think that David still thinks about pitching throughout the day. It’s a different life now, you’re retired. You have different things to do. But I firmly believe that his life’s passion is all about pitching.

JB: I’m reading just incredibly detailed ways on how to throw a two-seamer, or even how to take advantage of a scuff. He sounds like a coach or even a personal trainer.

JC: Oh, I think David Cone would make a terrific pitching coach. I’ve been asked this before. I think, first of all, he would walk onto the field and players would respect him immediately because of his career. Because he talks their language. Because he knows how hard the game is. And he also speaks the sabermetrics language.

He knows what high-speed cameras can do, he knows what spin access and different arm angles and all of that can do. He interviewed for the Yankees pitching coach job, but he didn’t end up getting it. I was told that he interviewed very well. But I think David, if he ever wanted to do it, would be a fantastic pitching coach.

Looking to 2020

JB: Last question, Jack. The 2020 season is unlike anything that we’re ever going to see in baseball history. Covid-19 is ravaging the nation, ravaging the world. What are your thoughts as baseball comes back next week and enters completely unfamiliar territory?

JC: Josh, none of us are blind to what is going on in the world. We all wake up every day and we realize that we are living in a different world. It’s a sadder world. It’s a world that has changed dramatically and that we hope we sort of get out of this nightmare. That preface, to me, almost goes without saying.

I think baseball in its own way, and it’s a different version of baseball– a far different version of baseball than we have ever seen, can provide some solace to people and some happiness to people. I can speak from personal experience just from working at the YES studios for the last couple of weeks where we’ve been broadcasting workouts and intrasquad games. Just the excitement people have shared with me on social media about how excited they are just to see an intrasquad at-bat between J.A. Happ and Aaron Judge.

We missed baseball. Coming back and saying you like baseball and that this is something you’re looking forward to doesn’t mean that you’re ignoring the coronavirus. I think it means that within the midst of this horrible time, we reach for things that bring us joy. And this different version of baseball is something that can bring people some joy.

Josh Benjamin has been a staff writer at ESNY since 2018. He has had opinions about everything, especially the Yankees and Knicks. He co-hosts the “Bleacher Creatures” podcast and is always looking for new pieces of sports history to uncover, usually with a Yankee Tavern chicken parm sub in hand.