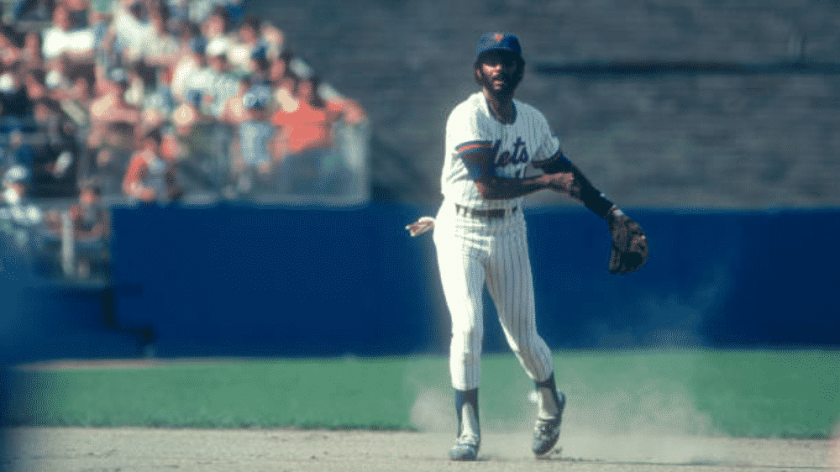

New York Mets greatest forgotten players: SS Frank Taveras

The New York Mets’ history at shortstop is grim, but it shouldn’t be forgotten. Frank Taveras is a perfect example of old school vs. analytics.

[sc name=”kyle-newman-banner” ]The New York Mets were not a good team in the late 1970s. After their miracle run in 1973, the Mets weren’t able to reach those heights again. That didn’t matter to management.

The Mets were always chasing the biggest names they could to regain that spark. At the start of 1979, the Mets were still searching for that spark again.

They were 3-7 after 10 games in the season and their starting shortstop Tim Foli only played three of the first 10 games leading to a move. The Mets traded Foli and minor leaguer Greg Field for speedster Frank Taveras.

Foli went on to have the best season of his career and helped the Pirates win the World Series. Taveras took his place at shortstop in New York where he brought the best of his brand of baseball.

The strong start

Taveras came to the Mets as one of baseball’s best base stealers. He had stolen 218 bases in the previous four seasons. The Mets hadn’t ever had a player steal 40 bases in a season.

Taveras was supposed to bring an element of speed that the Mets never had. He succeeded in bringing that speed to Queens, stealing 42 bases in 1979. That would be the Mets’ record until Mookie Wilson broke it in 1982.

At the plate, Taveras was nothing special but he wasn’t dead weight. He hit .263/.301/.331 and hit his only career over the fence home run off of Cincinnati Reds’ pitcher Mike LaCoss.

Taveras was everything the Mets thought they were getting when they made the trade even though he wasn’t enough to make New York a winner that season. They finished last in baseball with a 63-99 record. General manager Joe McDonald, who orchestrated the Taveras trade, was fired in February of 1980 just before the start of the 1981 season due to the team’s performance.

Decline and the strike

Taveras’ decline started in 1980. At 30-years-old, he began to lose his trademark speed and only stole 32 bases in 1980, which was his lowest mark since 1975.

Most ignored the decline in speed and stolen bases though because he hit better than he did in 1979. Taveras hit .279/.308/.327. That was the second-best season at the plate in his career. He set a career-high in batting average, his third-best OPS, and his second-best OPS+.

While the speed did drop off considerably, it didn’t matter. Taveras was still one of the best base stealers in Mets’ history and with an improved bat he looked like a fixture at shortstop until his contract was set to run out at least.

By 1981, Taveras was in full-blown decline. His speed was still there from the season before he stole 16 bases in 84 games, a 30 steal pace over 162 games. That was the only thing left though.

Taveras hit an awful .230/.263/.290 over the course of the season. An MLBPA strike ended the 1981 season after just 84 games.

After the season ended the Mets shipped Taveras off to the Montreal Expos for pitcher Steve Ratzer. The shortstop would retire after an even worse 1982 season and Ratzer would never throw an inning for the Mets.

Old School vs. New School

Taveras is a fascinating study of old school baseball versus the analytics age. In old school baseball terms, Taveras’ first two years with the Mets were good. He was a good old school leadoff hitter who didn’t get hurt, hit for average, and stole bases. He didn’t need to do much else other than that.

The analytics disagree with that. Taveras was worth just 0.3 fWAR in 1979 and -0.5 fWAR in 1980. He’s considered one of the worst hitting shortstops in baseball at the time because of his awful on-base percentage and power numbers. Not to mention, his defense was atrocious.

Taveras never had a three fWAR season and only topped two fWAR twice in his career. In modern baseball, he’s a backup shortstop who can provide speed off the bench.

In the 1970s and 80s, he was a starting shortstop for eight seasons split between two teams. It’s easy to see the differences in on-base and slugging that would make him nearly unplayable in modern baseball. What’s more interesting is how speed is valued in modern baseball.

Taveras was in decline when he was stealing 32 bases in 1980. That would have been sixth in MLB in 2019. Of the players that would have been in front of him, only two put up similar offensive numbers, Mallex Smith of the Tampa Bay Rays and Adalberto Mondesi of the Kansas City Royals.

Mondesi was a positive defender in 2019 worth eight DRS and four OAA. That made him a positive player worth 2.4 fWAR. He’s bringing speed and defense to the field so his inclusion in the lineup makes sense.

Mallex Smith is a different and difficult case. He was worth -13 DRS and six OAA in 2019. According to one metric, he was one of the worst defensive centerfielders in baseball and the other says he was one of the best. He was worth zero fWAR in 2019 after a strong 2018.

This is the key difference in how players are evaluated in modern baseball. Taveras’ speed was measured in stolen bases and his ability to change the game on the base paths. That’s not valued as much in the analytics age because stealing bases is an unnecessary risk.

Baseball has evolved to look at speed as a defensive metric that can change the game in different ways. It’s interesting to imagine Taveras and players of his ilk from the 70s and 80s in modern baseball.

Would they be able to adapt and put their speed to use defensively? Would they fade into obscurity because stolen bases are valued so much less, or would the stolen base become a valuable commodity once again?

A contributor here at elitesportsny.com. I'm a former graduate student at Loyola University Chicago here I earned my MA in History. I'm an avid Mets, Jets, Knicks, and Rangers fan. I am also a prodigious prospect nerd and do in-depth statistical analysis.