Yankees, MLB and the demise of the indispensable baseball scout

If they are not doing it already, it’s likely that colleges will soon be offering a degree in Baseball Sabermetrics. As the unstoppable train, analytics rule the game. But there’s a fallout attached to it, and it too is an unstoppable train.

The New York Yankees begin this piece as the subject with an excerpt from an article written by Jim Kreuz for the Society for American Baseball Research (SABR) reads as follows:

“When the last out was made, Mickey, his dad, and I got in my car behind the grandstand, and in 15 minutes the contract was signed. We agreed on $1,500 for the remainder of the season, and the contract (Independence of the K.O.M.) was drawn calling for a salary of $140 per month. Mickey reported to Harry Craft at Independence. He was slow to get started and as late as July 10th was hitting only .225 but finished the season over .300. The following year at Joplin he hit .383, I believe. You know the rest.”

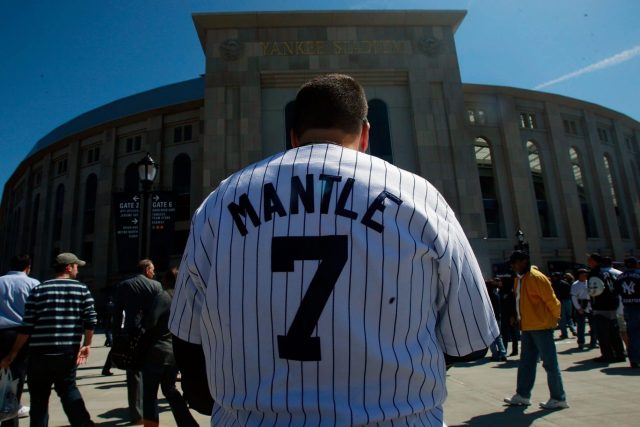

The “Mickey” is, of course, Mickey Mantle. The words, however, come from a man whose name may not be as recognizable, Tom Greenwood. Greenwood is best described as a traveling vagabond who was owned by no one. At that moment spoken about above, the trail brought him to Joplin, MO where he became fascinated by the youngster with the boyish grin and the strapping muscles. Greenwood reported his findings to Yankees general manager George Weiss, packed his bags and moved on to find more talent.

[sc name=”Yankees Center” ]Kreuz adds, for SABR, that Greenwood is also responsible for signing George Kell, Rex Barney, Cal McLish, Bill Virdon, Pee Wee Reese, Gil Hodges, Hank Bauer, Tom Sturdivant, Elston Howard, Ralph Terry, Bobby Murcer, and Jackie Robinson.

Tom Greenwood is not a super-scout. And that’s only because behind every Hall of Fame ballplayer, there was a bird-dog who saw him first. He witnessed “something” (more on that later) and signed him to his first major league contract. Just because.

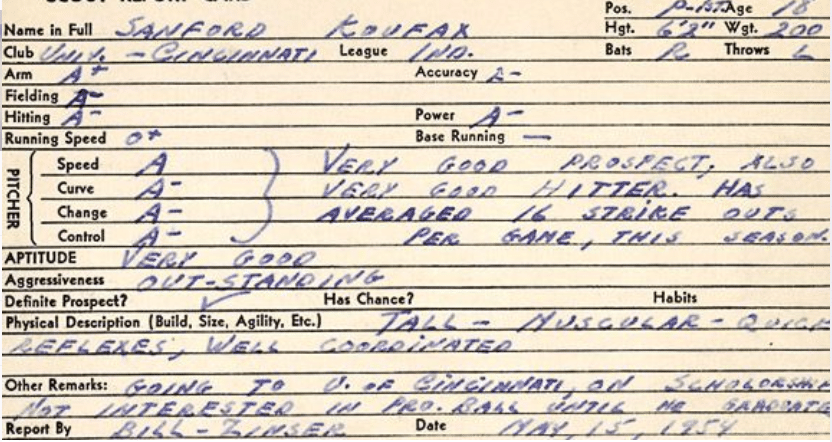

The Baseball Hall of Fame features an exhibit they appropriately titled “Diamond Mines”, which exists solely as a tribute to the dinosaurs who have walked this earth in the name of major league scouts. In that wing, you can find a treasure of documents like the one which appears here, the initial scouting report on Sandy Koufax.

Transitioning now to the point of this article, what is the destiny of the major league scout in a baseball world dominated by analytics? And is there a still a need for the men in the trenches when, theoretically, the numbers tell all?

I don’t know the answer, but I can tell you this. In 2004, I attended a Class-A game in Fishkill, NY, the home of the Hudson Valley Renegades, an affiliate of the Tampa Bay Rays. In the top of the first inning, my eyes were drawn to a young man in the on-deck circle who, with one glance, you just “knew” was made of the stuff a major league ballplayer should look like. He just had that “feel.”

That player turned out to be Josh Hamilton, who was coming off of one of his many suspensions for drug abuse. Fittingly, Hamilton struck out in that at-bat, but the lasting image of his stature and “look” remains impregnated in my mind.

Who is left to measure the intangibles?

The central question then is if we are moving ever closer to an era in baseball in which numbers of all kinds, plus numbers we haven’t even imagined yet, dominate the evaluation of baseball talent, who is left to measure those all-important intangibles?

Who is there, for instance, to note that Todd Frazier‘s .213 batting average didn’t outweigh the energy he brought to the Yankees when he arrived from the White Sox last season? And who is to say CC Sabathia will not be worth his measure in gold to the Yankees as a stabilizing factor in their starting rotation, even if he manages to win only ten games?

These are subjective questions that are not bound by the finite solutions of mathematics. But still, did the Yankees, in fact, gel as a team once Frazier arrived? I think so, but you may feel otherwise. And therein lies evidence of the abyss baseball may be creating for itself. Gimme numbers and I’ll tell you what you are worth?

And as further evidence here’s a link to job opportunities within the Yankees organization. Look closely, but you will not find anything even close to a scouting position.

[sc name=”Yankees Center” ]But it goes even deeper than that. Where was the scout like Greenwood, who watched Mickey Mantle develop for more than a year while keeping in close contact with Mantle’s dad…where was that for Josh Hamilton?

Because it can’t be assumed those addictive tendencies of Hamilton’s didn’t develop the moment he signed a major league contract as a first-round draft pick with the Tampa Bay Rays in 1999. Can they?

And if the disease had been diagnosed by a hawkeye scout, is it not possible some teams who crossed paths with Hamilton would have saved themselves a total of $140 million over the course of his career?

I said it was subjective and the argument can go either way as to whether or not Josh Hamilton (as only an example) shows the value of human contact with a prospective signee. And yet, there might be a reason why, according to Scooby Axson of SI.com, “A New York Yankees scouting report on retired shortstop Derek Jeter sold for $102,000 on Sunday, according to Heritage Auctions.”

[sc name=”City Stream” ]Baseball needs a balance

The old saying “you can’t fight City Hall” certainly rings true when it comes to baseball. And general managers across the breath of baseball have found a tool in analytics they never had before. Like any new toy, we can expect this one to get premium use for the time being.

This is not to subtract from the value of analytics, which is real and welcome. It is just to hold up a caution flag before there’s a crash on the final turn before heading down to the finish line.

Teams have only so much money to spend on administrative personnel. Chances are most of that allocated expenditure, even for the Yankees, is earmarked for staff with degrees in statistics and actuarial acumen.

But in the 21st century, does that have to automatically mean we are moving ever closer to a robot society, in which there is no value placed on human input into a player’s value or non-value?

I don’t believe teams, and especially the Yankees, will go that far. But it bears watching because if it should occur, major league baseball will have lost something that is irreplaceable, as scouts move on to other career endeavors or, more likely, other jobs out of baseball.

According to Wikipedia, the Yankees still employ 152 scouts in their organization. The question, though, becomes how loud their voice will be heard when it comes to judging talent.

I hope that Brian Cashman uses all of his power to incorporate these men and women into any discussion involving current or future Yankees player personnel, in addition to the avalanche of stats coming his way.. It only makes sense.

[sc name=”Yankees Link Next” link=”https://elitesportsny.com/2018/01/08/new-york-yankees-johnny-damon-deserves-carrot-hof-bone/” text=”Johnny Damon deserves a carrot, not a bone for the HOF” ] [sc name=”MLB Section” ]A fan of the Yankees for more than a half-century, the sport of baseball and writing about it is my passion.

Formerly a staff writer for Empire Writes Back, Call To The Pen, and Yanks Go Yard, this opportunity with Elite Sports NY is what I have been looking for.

I also have my own website titled Reflections On New York Baseball.

My day job is teaching inmates at a New York State prison. Happily married with five grandchildren. Living in Catskill, New York.