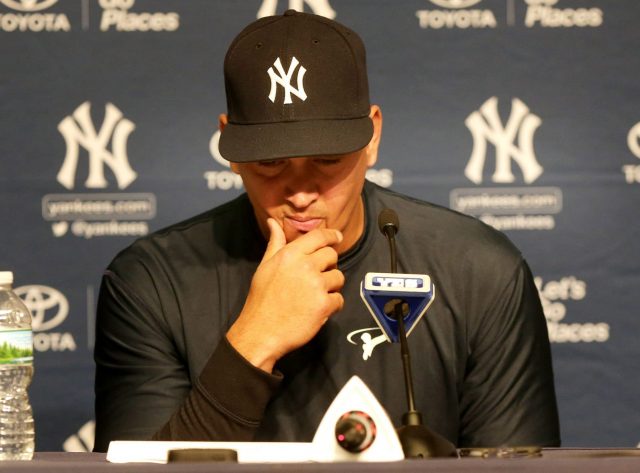

Alex Rodriguez: A New York Yankees’ Career Retrospective

Alex Rodriguez’s Yankee career, if not baseball playing career, comes to a close on Friday at the Stadium against the Rays. Ultimately, what is his legacy? The answer is not so clear.

[dropcap]B[/dropcap]y agreeing to a premature release from his playing contract with the New York Yankees, a gargantuan, ten-year pact, for which he notoriously opted out during the 2007 World Series, a bloated, polarizing deal that would have taken him through the 2017 season at age 42, Alex Rodriguez, as of Friday, will no longer don pinstripes as a player for the most storied club in professional sports.Instead, Rodriguez will serve as an adviser and consultant—for the $27 million he was due the remainder of this season and all of next—for players coming through the Yankee farm system, mainly based in Tampa, through December 31, 2017.

Unless he adds to his totals in limited action this week, A-Rod will fall four homers short of 700, nineteen shy of passing Babe Ruth for third-all time on the major leagues’ all time home run list.

Given his pitfalls and missteps, of which there were many, during his Yankee tenure, Rodriguez has been gifted a number of unpleasantries over the years.

A-Fraud.

A-Roids.

Pariah.

Villain.

The face of the Evil Empire.

Derek Jeter’s one-time bestie.

Not a “true Yankee,” whatever that distinction even entails.

A narcissistic pretty boy, whose off-field antics—galavanting shirtless around Central Park, his amorous connections to Madonna and Cameron Diaz, kissing himself in the mirror for a magazine spread, tossing his cousin under the proverbial bus for reportedly granting him access to steroids—made him a tabloid superstar, a paparazzo’s dream.

Amongst these aspersions, he has and never will be called what he truly is: a baseball immortal, and, as many detractors would begrudgingly admit, a Yankee legend.

Last season, he became the 29th player to eclipse 3,000 hits (quietly so: the Yankee organization reluctantly agreed to recognize the feat on September 13, 2015, three full months after the fact), a benchmark for a player to make the Hall of Fame. Other than Ichiro, who reached the mark on Sunday with a triple against the Colorado Rockies (he is a lock for Cooperstown), Pete Rose, banned from the game for ties to gambling, Jeter (also a lock), and Rafael Palmeiro, shunned by the Baseball Writers Association of America for ties to PEDs, every player who previously eclipsed the mark is in the Hall.

A true testament to his power, A-Rod mustered 15 seasons with at least 30 home runs, including 33 at age 40 (in 2015), a feat matched only by Hank Aaron for the most all-time.

Rodriguez’s 117.4 mark in Wins Above Replacement (WAR) for position players ranks 20th all-time (he is 13th all-time in Offensive WAR), second only to Barry Bonds (162.4) for players who played into the 21st century. All-time across Major League Baseball, he ranks eighth in runs scored (2,021), sixth in total bases (5,811), fourth in home runs (696), third in RBI (2,084), eighth in runs created (2,274), twentieth in adjusted batting runs (640), and sixth in extra bases hits (1,274).

He is arguably the greatest player of his generation, a would-be, first ballot Hall of Famer who could have made it to Cooperstown unanimously had it not been for his sordid, PED entanglements.

Alex Rodriguez will play his final game on Friday.

Take a look back at his MLB career.https://t.co/OZ9V1Sv0bq

— Baseball Tonight (@BBTN) August 7, 2016

Despite what he has accomplished in baseball, his fate may be similar to Bonds’s, Palmeiro’s, Roger Clemens’s, Mark McGwire’s, and Sammy Sosa’s: locked out of Cooperstown despite MLB gaining from, and largely neglecting, their alleged, rampant PED use.

While it was Cal Ripken’s passing Lou Gehrig’s consecutive games mark in 1995 that salvaged the game from the strike that cancelled the 1994 World Series, it was McGwire and Sosa’s assault on Roger Maris’s single-season home run record in 1998 that catapulted the game back to its pre-1994 levels of popularity.

While Bonds, McGwire, and Sosa could not be punished for their alleged ties to steroids—the game would not suspend PED users until 2004, A-Rod’s first with the Yankees that ended in catastrophe, a Red Sox World Series championship that came at the hands of Rodriguez’s Yankees blowing a 3-0 series lead in the ALCS—A-Rod could be penalized, and ultimately was in 2014, somewhat retroactively.

As for his time with New York, with his second American League MVP with the club in 2007, Rodriguez became the first Yankee in 46 years since Roger Maris to win multiple MVPs. By winning his second MVP, A-Rod joined Maris (twice), Mickey Mantle (thrice), Yogi Berra (thrice), Joe DiMaggio (thrice), and Lou Gehrig (twice) as the only players to win multiple MVPs with the Yankees.

All-time with the Yankees, Rodriguez ranks tenth in runs scored (1,012), sixth in home runs (351), eleventh in RBI (1,094), eleventh in stolen bases (152, remarkable, considering how his speed had decreased considerably not too far into his Yankee tenure), and seventh in OPS (.901).

With New York, A-Rod lead the American League in runs scored twice (’05 and ’07), home runs twice (’05 and ’07), RBI once (’07), slugging percentage thrice (’05, ’07, and ’08), OPS and OPS+ twice (’05 and ’07), and total bases once (’07). He also won the Silver Slugger three times and made the All-Star team seven times, the last of which came in 2011.

Never mind that A-Rod’s arrival in the Bronx forced him to shift from shortstop, where, even despite not playing there since 2003, Rodriguez will retire as one of the game’s greatest players at the position, a man whose power and athleticism redefined it.

Quite frankly, we will never see a shortstop quite like him.

Alex Rodriguez to the Hall of Fame? Here’s why it could happen (by @Jay_Jaffe) https://t.co/bCVfDTnaBR pic.twitter.com/8JpYLBB0Cb

— Sports Illustrated (@SInow) August 7, 2016

By deferring to then shortstop Derek Jeter, Rodriguez moved to third base—a transition he handled with grace and class—a position (other than designated hitter) for which A-Rod excelled as a Yankee, both with the glove and at the plate.

Had 2003 ALCS hero Aaron Boone not injured his knee playing pickup basketball in the offseason, perhaps the deal for A-Rod never happens.

To either the delight or chagrin of Yankee fans desperate to sustain and hold on to a dynasty that ended in disappointment with World Series losses to the Diamondbacks in 2001 and the Marlins in 2003, largely because of the Yankees’ lack of hitting, A-Rod was brought on to be a Yankee, and whether or not his naysayers will admit it, he delivered far more good times than bad.

Alas, however, the aforementioned mishaps have a great deal to do with his place amongst the greats in baseball.

Like Roger Clemens, Alex Rodriguez, in 2013, left Bud Selig’s New York based office, moments after lengthy litigious proceedings with the former baseball commissioner, and went on air with WFAN’s Mike Francesa, pleading innocence from any association with performance enhancing drugs, adamantly and vehemently so. The incident called into question Francesa’s credibility and, ultimately, A-Rod’s integrity: the results of subsequent hearings amounted to his getting suspended for the tail end of the 2013 season and the entirety of the 2014 season, Jeter’s last season in pinstripes.

While Jeter was warmly revered in city after city for his contributions to baseball, fans cannot expect the same as A-Rod returns this week to Fenway Park, a place in which he debuted as a major leaguer at 18 with the Seattle Mariners, a landmark where A-Rod’s face met Jason Varitek’s glove in an early season series against Boston in 2004, prompting a momentum shift in the AL East that ultimately ended in a Red Sox title, and plays his final game at Yankee Stadium on Friday.

The Francesa interview came after a cringeworthy sit-down with Peter Gammons in 2009, by which he admitted to steroid use after testing positive for steroids during a preliminary 2003 screening, a year before Major League Baseball would officially test and suspend players for PED use. Never mind that David Ortiz, currently receiving a hero’s welcome in ballparks all around America, a la Chipper Jones, Mariano Rivera, and Derek Jeter, was linked to that same 2003 test, and does not endure similar vitriol and disgust.

Although A-Rod only admitted to using steroids for a three year period, from 2001 to 2003, with the Texas Rangers, never once while in New York, the interview still did its part to taint the two American League MVPs he won in pinstripes, along with the Ruthian effort he put forth during the Yankees’ 2009 championship run.

As general manager Brian Cashman noted during Sunday’s press conference announcing A-Rod’s release/retirement, the New York Yankees would have never won that aforementioned World Series title in 2009.

During that playoff run, A-Rod, over fifteen games, behind some great performances from CC Sabathia, Mark Teixeira, and Mariano Rivera, almost singlehandedly carried the Yankees to their title over the Philadelphia Phillies, hitting .378 (he hit .455 in the ALDS against the Twins and .429 in the ALCS against the Angels), with a 1.331 OPS, six home runs, and eighteen RBI.

Fans of the game may never witness another performance quite like A-Rod’s masterpiece in 2009.

Alas, Rodriguez, a career .259 hitter in the postseason, whose poor play resulted in Joe Torre once batting A-Rod eighth, and whose nine strikeouts against the Baltimore Orioles in the 2012 ALDS amounted to his being benched by Joe Girardi in a decisive Game 5 of that series, was never, other than in 2009, a regular Mr. October, which drew ire from many Yankee fans, who watched a dynasty plug along off the clutch performances of Jeter, Bernie Williams, Paul O’Neill, Tino Martinez, Jorge Posada, and Scott Brosius.

Alex Rodriguez currently has 696 career HRs, 4th most on baseball’s all-time list. pic.twitter.com/YoyduIxinT

— Baseball Tonight (@BBTN) August 7, 2016

Unfortunately, Alex Rodriguez, a generational talent unlike any seen before in baseball history, never quite “fit” the mold of a superstar. He did not garner the international fame of a LeBron James, a Lionel Messi, a Cristiano Ronaldo, or a Michael Jordan.

He was insecure, and could never hold the mantle of Yankee captaincy or stardom quite the way his pal Jeter had.

He was never known as a clubhouse leader until 2015, when, a year away from baseball due to suspension, A-Rod was forced to “play nice” for the sake of preserving his reputation and namesake, which he accomplished genuinely and seamlessly; this, two years removed from Rivera’s retirement, one year after Jeter’s departure from the game, when New York no longer had its “face of the franchise” it has enjoyed decade after decade.

Despite a relative return to his old ways in 2015—he hit 33 homers with 86 RBI, leading the Yankees to their first playoff berth in three years—even A-Rod could not be that face of the Yankees that left with Jeter’s exodus. That “face of the Yankees” will likely not be fulfilled, even beyond next year, until one of the young players from the farm system that Cashman replenished rises above to grasp that proverbial title.

A-Rod’s departure, along with Teixeira’s retirement announcement last week, ultimately bids farewell to all that remained of the 2009 title team (as players, only Sabathia and Brett Gardner are still aboard), ushering in what could be another Yankee dynasty, with the perfect storm of parting contracts, an influx of youth, and a terrific free agency window all amassing together in 2018, when A-Rod’s duties as consultant and player adviser are through.

With enough distance between A-Rod’s leaving the game and his potential Hall of Fame candidacy in five years, baseball writers may eventually come to their collective senses and award Rodriguez his rightful place in Cooperstown, with a catch, of course: while voters can deny his numbers for only so long, they cannot deny A-Rod’s ties to PED usage, which ought to, when and if it occurs, be emblazoned on his Hall of Fame plaque.

[sc name=”Yankees Center” ]In 2016, his fourth year of eligibility, Bonds enjoyed his highest percentage of voters placing his name on the ballot (44.3%), a gradual climb from the 36.2% he earned in 2013. Though Bonds is nearly 31% short of the percentage needed to enter the Hall, he has been making headway, and has not slipped in percentage the way other contemporaries have. If there is hope for Bonds, there remains hope for A-Rod, although the latter’s road is a bit tougher, considering he cheated while rules were already established to bar PED users.

Although A-Rod is not the transcendent player Bonds is—quite frankly, Bonds knows no equal in the game’s history, save perhaps for Babe Ruth and Willie Mays—he remains one of the top 20 players the game has ever seen, and one of the best right-handed hitters and shortstops the game will ever see. In short, only Honus Wagner fielded the position better than Rodriguez.

A-Rod’s imminent departure is a sigh of relief, as the Yankees will no longer be bound to a contract that has floated above the organization like a black cloud from the moment Rodriguez was extended in 2007, especially since he never returned to his MVP numbers of that season, even if he did help deliver a World Series in 2009.

Regardless of all the bad tidings surrounding Rodriguez, there is no denying his place in the game and its history. Villain or hero, Alex Rodriguez crafted a legacy that will resonate well beyond his bittersweet departure on Friday, a legacy largely galvanized during his time as a New York Yankee.

Featured Image via Andy Marlin of USATSI

NEXT: Hal Steinbrenner Maintains A-Rod’s Decision Didn’t Come Via Ultimatum

I am an English teacher, music and film aficionado, husband, father of two delightful boys, writer, sports fanatic, former Long Islander, and follower of Christ.

Based on my Long Island upbringing, I was groomed as a Yankees, Giants, Rangers, and Knicks fan, and picked up Duke basketball, Notre Dame football, and Tottenham Hotspur football fandom along the way.