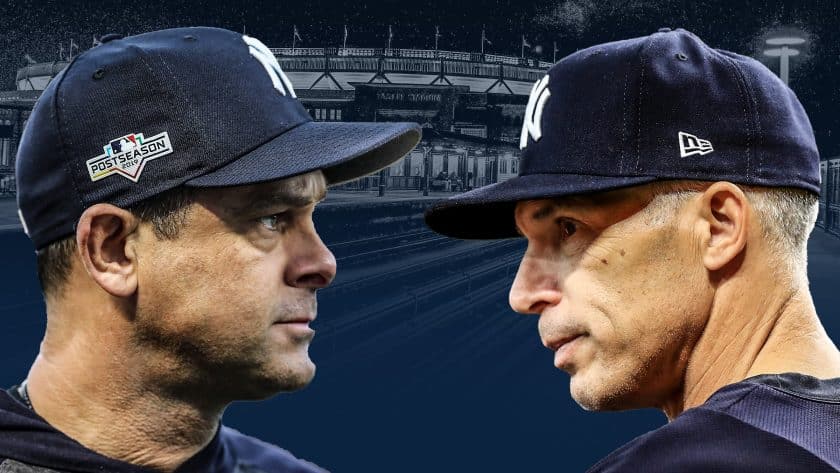

The newest mantra for the Girardi and Boone era Yankees: wait until next year

Of late, the New York Yankees have bowed out to superior competition in the Houston Astros (twice) and the Boston Red Sox, two would-be World Series champions. How do the Bombers work to achieve Houston and Boston’s latest successes?

[sc name=”Bryan Pol Banner” ]Impressing New York Yankees fandom onto your sons is equal parts a joyous art form and an arduous task.

For my boys Eric and Adam, some four years ago, I first had to sell them on baseball before I could instill them with an ardor for the Bronx Bombers in much the same way my parents did for me throughout the eighties and nineties. For my parents, the task was much easier:

- The Yankees of my formative years had star power. Pick “your guy” to vehemently follow, a simple task, considering just how many there were: former MVP Don Mattingly, a maestro with the glove; Dave Winfield, who battled Donnie Baseball until the season’s last day in 1985 for the AL batting title; Rickey Henderson, whose stolen base records will never be eclipsed, given the nominal attention paid to “small ball” in baseball today; Bernie Williams, a stud outfielder from Puerto Rico who carried on the tradition of stout pinstriped centerfielders in the mold of Mantle and DiMaggio; the Core Four of homegrown prospects in Derek Jeter, Andy Pettitte, Jorge Posada, and Mariano Rivera, two of whom are mortal locks for enshrinement in Cooperstown; Paul O’Neill, the very epitome of grit and fervor; Tino Martinez, who so capably replaced Mattingly at first with both the bat and glove. For a two-decade span, the New York Yankees were comprised of stars and characters both compelling and polarizing.

- The old Stadium contained mystique and volume. Look no further than Gary Thorne’s call of Don Mattingly’s home run in Game 2 of the 1995 American League Division Series, the first of its kind, against the Seattle Mariners for proof of just how ebullient the place once was. Much of this had to do with the Yankees not making the postseason for fourteen years, the first of Mattingly’s career, but the Stadium seats back then could still be afforded by diehard fans who have since been priced out of prime viewing engagements. What once went for $150 (behind the plate!) can now be purchased for $2,500, and that is during the regular season.

- The Yankees, back then, won championships. George Steinbrenner’s suspension from baseball in the early nineties permitted Gene Michael to place emphasis on building a farm system that resulted in Bernie, Jeter, Pettitte, Rivera, and Posada’s arrival in the Bronx, along with pieces (like Roberto Kelly) to yield mainstays in the lineup (see Paul O’Neill). This notion, along with shying away from trading away prospects en masse for the next Ken Phelps, while committing to spending, resulted in a dynasty that spanned 1995 to approximately 2003, a time frame that produced seven division titles, six American League pennants, and four World Series championships (even the Core Four remained intact for a fifth title in 2009). Alas, in light of the recent ALCS loss to the Houston Astros, the Yankees failed to reach the Fall Classic for an entire decade, the first time that has occurred since the 1910s.

In 2015, with my sons Eric and Adam, then aged eight and five respectively, I opted to take my family to the final game of the New York Mets season at Citi Field, a Sunday that coincided with the Mets’ officially clinching the NL East division and my sons’ being able to walk on the field and run the bases. It goes without saying that tickets back then were cheap. On that day, I inadvertently bumped into legendary announcer Gary Cohen on the way through the corridors to exit (alas, I froze in his presence) and subsequently triggered Eric’s interest in baseball (Curtis Granderson‘s late homer and Jacob deGrom‘s presence on the mound served me well), in a season where the Yankees eked into the playoffs via the wild card play-in game, their first taste of October defeat at the hands of the Astros (a loss that would be triplicated over time).

That Yankees team featured a reliever (Dellin Betances) leading the club in Wins Above Replacement, Didi Gregorius’s being expected to replace a legend at shortstop, with Brett Gardner and Luis Severino as the only homegrown mainstays on the roster, the former serving as the proverbial “face of the franchise,” a captain-less organization (Jeter retired the previous year) comprised of gargantuan, albatross contracts (see Mark Teixeira, Alex Rodriguez, Brian McCann, and Jacoby Ellsbury, the latter not appearing in the wild card game despite his sound health and a ledger that would demand he play) that was mired in controversy both clandestine (CC Sabathia‘s bout with alcoholism) and public (A-Rod’s first season removed from a year-long PED-incited suspension). It was difficult to purchase tickets at a high cost for a family of four to witness a team in relative turmoil and controversy, never mind that much of our funds made a trip to Europe possible in 2014 and a jaunt to China a reality in 2017.

By 2016, the club would opt to sell at the deadline, delivering closer Aroldis Chapman to the Chicago Cubs for a player, Gleyber Torres, who turned out to be a franchise cornerstone, with other pieces like Carlos Beltran, Andrew Miller, and Ivan Nova departing in favor of deepening a farm system, with Clint Frazier returning as the “top” haul (more on him later). That same team would bid farewell to Teixeira and Rodriguez at season’s end as Aaron Judge, Greg Bird, and Gary Sanchez debuted to much fanfare, the latter nearly edging Michael Fulmer for the American League Rookie of the Year. As fortune would have it, the Miller and Chapman trades altered the course of the 2016 postseason, with the Cuban fireballer Chapman factoring mightily in terminating the Cubs’ 108-year championship drought and the lefthander Miller helping push the Cubbies to a seventh game in that classic World Series.

By the time 2017 beckoned, I had made it official: I would be returning to the new Yankee Stadium for the first time in eight years (in the new cathedral’s inaugural season, I attended three Yankee games, a year before my firstborn son came into our lives), taking Eric and my mother Denise for their first-ever experience in the new digs on River Avenue, both for their birthdays.

On the weekend we went, Major League Baseball contributed its first Player’s Weekend experience as the Yankees faced off against the Mariners in Sonny Gray‘s Stadium debut and Ellsbury’s (likely) final time homering in pinstripes, a 6-3 victory featuring in the midst of Judge’s Rookie of the Year campaign and assault on our collective hearts and fan-going interests.

The timing could not have been more opportune in commanding my son’s zeal for the Yankees: he fell in love with the Stadium’s aesthetic (who doesn’t?) and immediately called upon Aaron Judge as his idol and hero. It certainly helped that New York enjoyed a fast-track rebuild that saw them fall a game short of the 2017 World Series en route to thwarting the Minnesota Twins, the Yankees’ whipping post for the better part of this century, and the Corey Kluber-lead Cleveland Indians, who fashioned a 22-game winning streak, entering October as the relative “team to beat.”

Even despite vying against, and ultimately losing to, a juggernaut offense in the 2018 Boston Red Sox and navigating innumerable injuries and scandals (see Domingo German) this season, Eric and I entered this October with high hopes, supporting the proverbial “Savages” who boasted a top offense (first in the majors in runs scored and second in homers, eclipsing their own record mark from 2018) and a tremendous bullpen that could compensate for only having three starting pitchers comprised of one certainty (the fearless-in-October Masahiro Tanaka), one newbie to postseason baseball (James Paxton), and an uncertainty (Severino) who barely pitched in 2019, and performed to much detriment in October in years’ past.

By Game 4 of the ALCS, however, we were riding an undercurrent of doubt: after losing a crushing extra-innings affair in Game 2 in Houston, the Bombers lost to AL Cy Young hopeful Gerrit Cole despite having him on the ropes (he would permit five bases on balls, his first time doing so since earlier in 2018). Even with the matchup in New York’s favor, Tanaka against Zach Greinke, whose postseason ledger outside of his tenure with Los Angeles is quite harrowing, something had not settled right, as the Yankee bats fell silent in the wake of Judge’s fourth-inning, go-ahead blast in Game 2.

By the third inning, Tanaka’s hot start was stifled by George Springer‘s three-run shot, the thirteenth of his playoff career, giving Houston a lead they would not relinquish. By the time I sent Eric to bed, Chad Green would surrender another three-run blast, forcing my son, who was still listening to the game through the crack in his bedroom door, to bludgeon the wall, with even a late Gary Sanchez homer having little to do in the way of effacing the four errors that defined New York’s 8-3 loss despite forcing Greinke’s early exit.

While we could chalk up losses in Game 3 and 4 to facing a behemoth in Cole and succumbing to utterly putrid play, the Yankees were in every last game, from the tone the Yankees set early in a thrilling 4-1 win in Game 5 to DJ LeMahieu‘s ultimately trumped heroics in the ninth inning of Game 6.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Uc_skJNxOCQ

In the end, the Yankees could not compensate for a multitude of issues:

- Their pitching was not on Houston’s level. Even with Tanaka and Paxton’s sterling efforts in Games 1 and 5, New York’s lineup was neutralized, largely off the efforts of Justin Verlander (Game 2), Cole (Game 3), and relievers coming through in massive spots. Aside from Green’s hiccups in Games 4 and 6 (Yuli Gurriel slayed him with a first-inning, three-run home run in spite of his dreadful postseason—he had been hitting .050 prior to that fatal swing) and Adam Ottavino‘s woes, New York went toe-to-toe with Houston on the mound, but ultimately conceded to what was a better staff, top to bottom.

- Their lineup, once defined by power, was short on depth. No question, Houston’s lineup, comprised of “been there, done that” superstars in Jose Altuve, Springer, Carlos Correa, and Alex Bregman, was the defining force in what was supposed to be an ALCS for the ages. Aside from LeMahieu, Torres, and some last-ditch magic from the likes of Hicks and Gio Urshela in Games 5 and 6, the Bombers’ lineup was as quiet as they had been all season. In essence, though, this has as much to do with Houston’s spectacular pitching as it has to do with a Yankee lineup that had not been short on thrills and a supreme ability to execute with runners in scoring position, a facet through which they dominated all season long, including an ALDS sweep of the Twins, the first such sweep of a team with 100 wins or more. Alas, those mighty efforts vanished after Game 1 of the ALCS, a victory that, unfortunately, did not set the tone for the series.

- General manager Brian Cashman failed to do it “his way.” Brian Cashman was intent on avoiding the luxury tax (Hal Steinbrenner’s orders), forcing him to deny Patrick Corbin a sixth-year in a prospective pact this offseason, settling instead to re-sign J.A. Happ, who ultimately lost his spot in the rotation and yielded the Correa bomb that ended Game 2 of the ALCS despite a strong showing (two scoreless innings) that kept the Yankees in Game 6. Happ will be 38 at the end of a contract that pays him $17 million annually, a player likely worth dumping this winter. In 2018, Houston GM Jeff Luhnow acquired Gerrit Cole, his starter for Game 1 of the World Series, despite Cashman’s efforts to offer the likes of Miguel Andujar, Clint Frazier, Chance Adams, and other prospects to procure the former Pittsburgh product. It turns out Luhnow’s package was substantially less than Cashman’s in terms of quality and players offered, leaving the Yankees on the outside looking in this week, as Corbin and Cole contend for this year’s title. Moreover, as this July’s deadline transpired, Houston acquired Greinke and the crosstown Mets landed Marcus Stroman, while the likes of Madison Bumgarner and Zack Wheeler remained in San Francisco and Queens respectively, forcing Aaron Boone to contend with what he had in Tanaka, Paxton, and Severino, as ten other pitchers ultimately rounded out the ALCS roster, some of whom (Ottavino, CC, and Happ) were either unreliable or questionable, given injury (see Sabathia’s early exit in Game 4). While players like Michael Tauchman, Gio Urshela, and DJ LeMahieu made Cashman look brilliant, it is where he failed to acquire starting pitchers that leaves New York empty-handed for a tenth consecutive year.

Despite the eventual defeat in the ALCS, Boone and Cashman, fresh off two straight 100-win campaigns, enter this winter in a somewhat enviable position.

In light of his subpar performance in the ALCS, Edwin Encarnacion is a likely victim of roster configuration, as may be Didi, who hit .190 in September and mustered an unremarkable .217/.217/.261 slash line in the ALCS, Brett Gardner, coming off a career year at age 35, Dellin Betances, whose torn Achilles mars any chance at pitching any earlier than August, Austin Romine, and Cameron Maybin, another unlikely surprise in Giancarlo Stanton‘s extended absence.

These subtractions, combined with Sabathia’s retirement and Chapman’s potential opt-out, clear just a shade over $75 million from the Yankee payroll (before arbitration), according to Baseball-Reference, permitting the club to spend in free agency to acquire starting pitching (Cole, Bumgarner, and Wheeler are all free agents, and Stephen Strasburg can opt-out of his contract in the next two offseasons) or even pursue Anthony Rendon, though they would be better served preserving Urshela as their option at third base, with Miguel Andujar looming as an option at designated hitter or as a trading chip (along with Clint Frazier) for another pitcher or star player on the block, like Cleveland’s Francisco Lindor (though they may be better served playing Gleyber Torres at short, his natural position, and moving LeMahieu to second while Luke Voit returns to man first base). For what it may be worth, Urshela and LeMahieu provide flexibility that the organization had not anticipated heading into 2019, players that all but shore up a much-improved infield that flourishes behind the plate and on the field.

No question, Didi Gregorius is a fan favorite, only just turning 30 at next season’s onset. Though injury precluded such ability in 2019, Didi’s lefty swing is tailor-made for the short porch in right, as evidenced by his peak year in pinstripes in 2018, when he managed 27 homers and a WAR mark of 4.7. Should both CC and Gardner leave, Didi is a leader the club can turn to, now having been part of every postseason roster since Jeter’s departure. When healthy, he adds depth to the lineup, though he is more “boom or bust” than he is a contact option for Boone. Not many in the fanbase would grimace over a reasonable three- or four-year contract to retain Gregorius, but can Didi rebound from a relatively quiet 2019? Would Thairo Estrada be a better option to spell Torres and LeMahieu in the middle infield at a fraction of the cost?

Gardner, too, is revered amongst the fans, but re-signing him to fill the role of a fourth outfielder (New York is already committed to Stanton, Hicks, and Judge) excludes two players—Tauchman and Frazier—who deserve a shot at his position, a healthy competition that could force Stanton to platoon between leftfield and DH. As Tauchman demonstrated, he could also fill Hicks’s spot when necessary, ably manning the centerfield position for fourteen games (eleven starts) in 2019.

Any decision over either Didi or Gardner, who started a relative revolution and rally cry, will not come easily, especially given the intangibles and clubhouse presence both provide.

Hypothetically speaking, with CC and Gardner’s potential absences, the Yankees relinquish leaders and clubhouse stalwarts, forcing the franchise to call on Aaron Judge and Gleyber Torres to fulfill such vacancies, though both look primed to grasp the opportunity. That said, Gary Sanchez’s fading down the stretch (likely in part of another groin injury that felled him for two straight years) and Stanton’s contract, health, and lack of performance leave the fanbase restless and fretful that the club can mimic what the offense has accomplished in 2018 and 2019.

Whatever the Yankees brass ultimately decides, Plans A, B, and C should begin and end with committing to Gerrit Cole, so long as the club is willing to move on from pitching coach Larry Rothschild and call upon a guru in the vein of Houston’s Brett Strom, who revitalized Cole and Verlander as veritable aces the past two years. With Cole leading the charge and Tanaka, Severino, Paxton, and Domingo German, pending a suspension, in support of him (or with Wheeler or Bumgarner replacing the latter, depending on the severity of his transgressions), the Yankees, with a blossoming lineup and stout bullpen, could have the answer that urges them past Boston, Houston, and the like en route to the 28th World Series that has eluded them the past ten years, emphatically quieting the “wait until next year crowd.”

[sc name=”Yankees Link Next” link=”https://elitesportsny.com/2019/10/22/new-york-yankees-deviated-from-savage-ways-this-postseason/” text=”The New York Yankees Deviated From Their Savage Ways” ]I am an English teacher, music and film aficionado, husband, father of two delightful boys, writer, sports fanatic, former Long Islander, and follower of Christ.

Based on my Long Island upbringing, I was groomed as a Yankees, Giants, Rangers, and Knicks fan, and picked up Duke basketball, Notre Dame football, and Tottenham Hotspur football fandom along the way.