On The Fence: The case for, and against, seven ‘borderline’ MLB Hall of Famers

The National Baseball Hall of Fame Class of 2018 will be announced Wednesday at 6 p.m. ET and there are several players whose chances remain tenuous.

The National Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown celebrates the history of the sport and some of the greatest to ever play the game.

However, as the years go by, we see more controversy and more arguments about who should and should not be inducted.

The steroid era has had an effect on the candidacy of players like Barry Bonds, Roger Clemens, Sammy Sosa, Manny Ramirez, and more, who are all undoubtedly Hall of Famers if the aura of their “cheating” did not exist.

It is up to the voters to decide how they feel about alleged steroid users being in the Hall – we all know how Joe Morgan feels. Yet baseball fans cannot believe they are seeing players like Vladimir Guerrero and Edgar Martinez still trying to gain entry on yet another ballot.

So I’ll handle it from here.

[sc name=”MLB Center”]

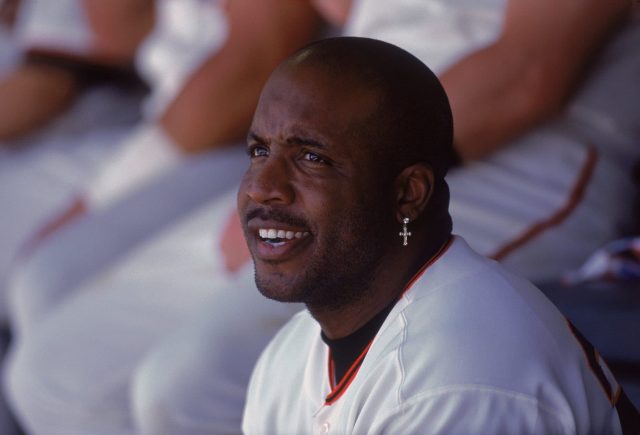

Barry Bonds

Why he belongs

Bonds was a seven-time MVP and became the disputed home run king on Aug. 7, 2007, hitting No. 756 to surpass Hank Aaron, who many still consider the true career leader. Along with his insane power, he had 514 stolen bases – 445 of them coming from 1986-1998.

He also holds MLB records for most walks (2,558) and intentional walks (688) while driving in the fifth-most runs ever (1,996). He’s also the only player in MLB history with at least 350 home runs and 350 stolen bases.

Bonds’ career on-base percentage was .444. He led MLB in OBP seven times and was the National League leader 10 times, including four consecutive years from 2001-04 (all MVP seasons) and again in 2006 and 2007, his final two seasons.

Yet the 2004 season might be Bonds’ best—and most bizarre season—ever. He slashed .362/.609/.812. Yes, a .609 OBP. But he only had 135 hits – and he recorded more times on base (382) than he did at-bats (373). He walked 232 times, 120 of them intentionally. Todd Helton, whose 127 walks were second-most in MLB that season, finished more than 100 behind Bonds.

Oh, and he was an eight-time Gold Glove Award winner.

Let’s face it – Bonds has the most incredible stats anyone has ever seen.

Why he doesn’t belong

The numbers above might not be, and probably aren’t, legitimate. Although it has never been proven, and he has never admitted it, all signs point to Bonds’ taking performance-enhancing drugs. His claims remain that his body blew up due to legitimate supplements, hard exercise, and a new diet.

Roger Clemens

Why he belongs

Clemens was one of the best pitchers of three separate decades. Nobody wanted to face him, and he wasn’t afraid to throw at anyone.

MLB’s ERA leader in 1990 (1.93) and 2005 (1.87), he won seven Cy Young Awards, his first in 1986, his last in 2004. His 354 career wins rank ninth all-time. He led the American League in ERA seven times, was an 11-time All-Star, a five-time strikeout leader and averaged 205 innings a season.

Perhaps most impressively, he won back-to-back AL Pitching Triple Crowns with Toronto in 1997 and 1998, going a combined 41-13 with a 2.33 ERA and 563 strikeouts.

Why he doesn’t belong

Clemens was listed in the Mitchell Report in 2007, along with 88 other players. Jose Canseco mentioned Clemens in his controversial book “Juiced,” but later backed off claims that Clemens used steroids. “The Rocket” has never admitted to using any performance enhancers and was even found not guilty on six counts of lying to Congress, where he again claimed his innocence.

Still, the cloud of suspicion remains.

Edgar Martinez

Why he belongs

Martinez was a seven-time All-Star and two-time AL Batting Champion, in 1992 (.343) and again in 1995 (.356). He led the AL in OBP three times, hit .300 or better 10 times—including seven-straight seasons, from 1995-2001—and compiled a career .312 batting average over his 18-years in the big leagues. He is widely regarded as one of, if not, the best designated hitter of all-time.

Why he doesn’t belong

He hardly ever played the field for more than half of his career and never won an MVP when he essentially had just one job. You can make the argument that his time as an “elite player” was roughly seven years (1995-2001)—which isn’t long enough to join the game’s truly elite in Cooperstown.

Trevor Hoffman

Why he belongs

A seven-time All-Star, his 601 saves are second all-time to only Mariano Rivera. He finished among the top six vote-getters for NL MVP four times and finished his career with a 2.87 ERA, 1.06 WHIP and 9.4 K/9.

Why he doesn’t belong

He very rarely pitched more than one inning, throwing 1,089.1 career frames over 1,034 games. Would he have been as effective in a different role? And while he racked up the saves, he was a part of only three playoff teams over 18 seasons. Was he really that valuable to his team?

Mike Mussina

Why he belongs

Notching 270 wins in the steroid era should not be something to ignore. He pitched in the American League East during the 90s and 2000s, two decades that were completely dominated by the Yankees (his second team) and the Red Sox, whom he faced every year as a player. He was a five-time All-Star in one of the toughest eras of baseball and was one of the best defensive pitchers of recent memory with seven Gold Gloves.

Why he doesn’t belong

He never led the AL in strikeouts or ERA, never won a Cy Young Award and each of his All-Star appearances came in the first nine years of his 18-year career. His ERA in his career was a 3.68, which is not astounding, and he averaged less than 180 strikeouts per 162-game season. If we’re going to call his prime from 1991-2001, his 3.49 ERA and 7 K/9 certainly makes him a questionable Hall of Famer.

Omar Vizquel

Why he belongs

He’s arguably the best fielding shortstop ever. He won 11 Gold Gloves and accumulated 2,877 hits. If Edgar Martinez might get in only for offense, why should Vizquel be punished for being special on defense?

Why he doesn’t belong

Well, he wasn’t great on offense. Yes, almost 2,900 hits are great, but that number over 24 seasons and accompanied by a .272 batting average certainly is not. Vizquel hit more than 10 home runs just once and never drove in more than 66 runs. Sure, Martinez gets praise for offense and no defense, and Vizquel will be punished for superb defense and mediocre offense, but offense wins. Three All-Star appearances in 24 seasons is not a Hall of Fame ratio.

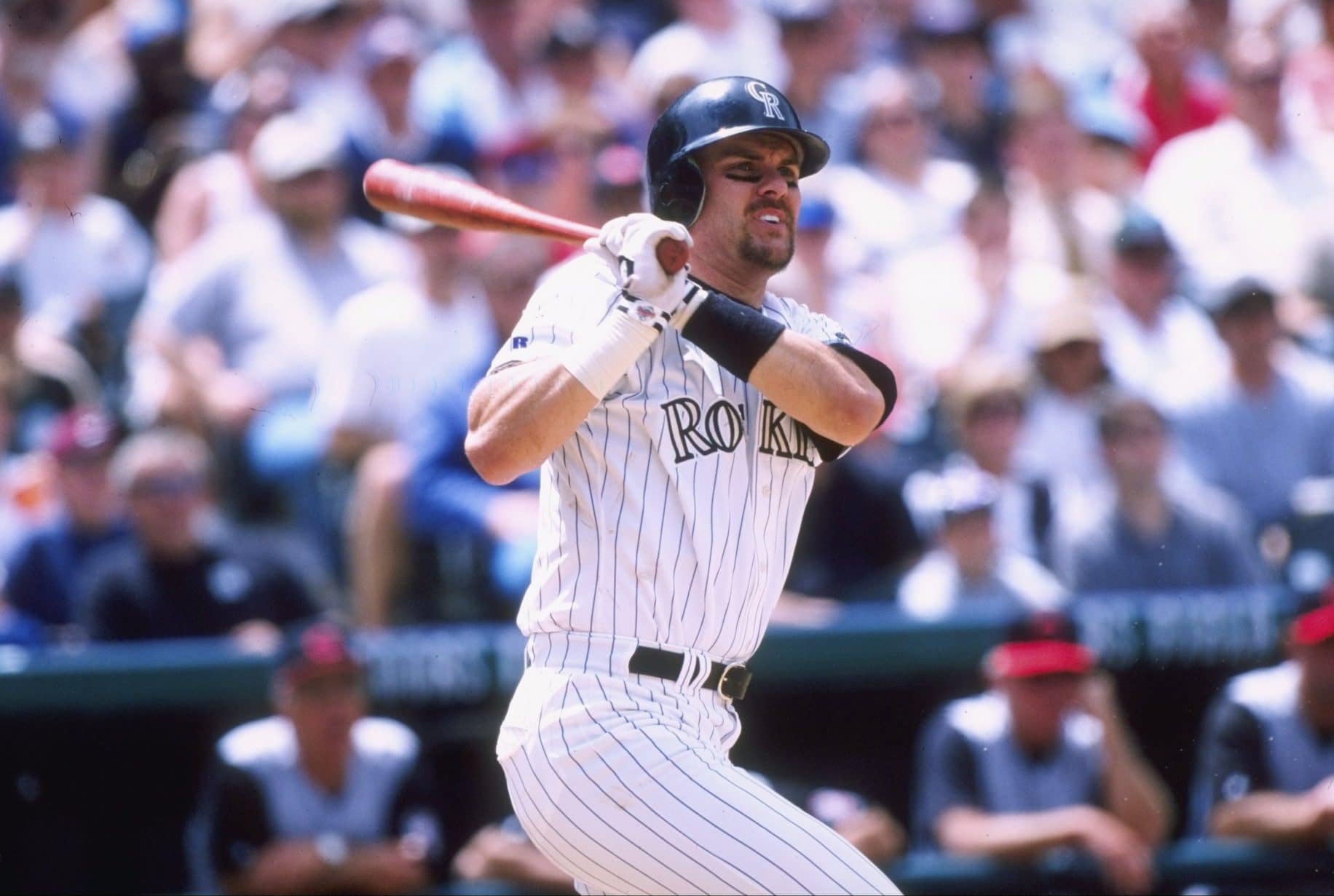

Larry Walker

Why he belongs

He has a higher batting average, more home runs, and more RBI than Martinez, who’s been beating him on every ballot, in almost 200 fewer games. Walker led the league in average three times, won an MVP, and averaged 36 HR, 119 RBI, and a .331 batting average from 1994-2004. From 1997-2002, he hit .353, had an OBP of .441, and averaged 39 HR and 124 RBI in a 162-game season. He also won seven Gold Gloves and finished in the top 10 in MVP voting four times.

Why he doesn’t belong

The bulk of his production came in the cozy confines of Coors Field, where he slashed .381/.462/.710 with 154 HR and 421 RBI over 597 games. He was somewhat injury prone and his power outside of Colorado was inconsistent at best.

Curt Schilling

Why he belongs

Schilling amassed 300 strikeouts three times and was a top-four finisher in the Cy Young Award voting four times. From 1997-2004, he had a 3.24 ERA and averaged 266 strikeouts per a full season. He also won two World Series in that time span, including splitting the 2001 World Series MVP with Randy Johnson. Schilling was the go-to guy in big spots (that damn bloody sock), and he led the National League in complete games four times – not easy for a pinch-hitter friendly league.

Why he doesn’t belong

His 3.46 ERA doesn’t exactly stick out. He has been in the headlines with lots of his mannerisms, and the Hall of Fame has been trying to shy away from those who might have tarnished their legacy because of their questionable actions and beliefs that the voters might not believe in. From 1997 to 2003, which was the height of Schilling’s career, he only had three seasons with an ERA of less than three, and the lowest ERA he had in that stretch was 2.95. Despite the controversy behind Schilling, he might be getting the Jack Morris effect – big-game pitcher votes, but it is in question if those votes are truly deserving.

[sc name=”Generic Link Next” link=”https://elitesportsny.com/2017/11/30/esny-2018-baseball-hall-of-fame-vote-cooperstown/” text=”ESNY’s MLB Hall Of Fame Vote” ]